1125899906842622

-

Challenge Author: ewang

-

Challenge Description: I found this credit card on the floor!

Reconnaissance

To begin we are given a very brief python script. Here it is in its entirety:

a = int(input())

t = a

b = 1

c = 211403263193325564935177732039311880968900585239198162576891024013795244278301418972476576250867590357558453818398439943850378531849394935408437463406454857158521417008852225672729172355559636113821448436305733721716196982836937454125646725644730318942728101471045037112450682284520951847177283496341601551774254483030077823813188507483073118602703254303097147462068515767717772884466792302813549230305888885204253788392922886375194682180491793001343169832953298914716055094436911057598304954503449174775345984866214515917257380264516918145147739699677733412795896932349404893017733701969358911638491238857741665750286105099248045902976635536517481599121390996091651261500380029994399838070532595869706503571976725974716799639715490513609494565268488194

verified = False

while 1:

if b == 4:

verified = True

break

d = 2 + (1125899906842622 if a&2 else 0)

if a&1:

b //= d

else:

b *= d

b += (b&c)*(1125899906842622)

a //= 4

if verified:

t %= (2**300)

t ^= 1565959740202953194497459354306763253658344353764229118098024096752495734667310309613713367

print(t)So the program takes in a number from us which then determine what operations happen on the number b. The program looks at the last two bits of our input number a, and determines 4 possible operations to occur. The 4 are:

- Multiply

bby 2 - Multiply

bby 1125899906842624 - Divide

bby 2 - Divide

bby 1125899906842624

Using these 4 operations we are trying to get the number b, which starts at 1, to reach 4. The final and biggest obstacle is that after every one of our four operations, the result of b bitwise AND c is multiplied by 1125899906842622 and added back to b. This operation becomes very annoying as whenever b&c isn’t equal to 0, b changes by an incredible amount and essentially becomes uncontrollable to be back on track to get to 4 with our limited operations. So, using our 4 operations we want b to reach 4 and avoid b&c equaling a nonzero number whenever possible.

From here if done right, the problem is solvable simply using something like dfs and pruning correctly to avoid times when b&c != 0, repeating moves, etc. However, I believe there is a more elegant solution that requires an important observation that may not be immediately obvious to some. At first the only additional thing I could come up with is that the other number that b can be multiplied/divided by of 1125899906842624 is actually 2^50. So now we have b which starts at 2^0=1, we want to reach 2^2=4, we can multiply and divide by 2^1 or 2^50 however we choose. Breaking it into powers of two is very important in understanding what is really happening in this challenge.

Solution

Eventually after being stuck for a while a teammate of mine said: “I think this is sort of similar to maze solving. We want to avoid the ‘walls’ of 1 bits because theyll screw up our b.” This was the key observation I was missing in the challenge and it ties together the significance of the c constant and our powers of 2. If we imagine this problem purely in terms of binary we can see the maze described. Because we move along powers of 2 our number is always a single bit, it is just a matter of where it is shifted. Multiplying and dividing by 2 is the same operation as a bitwise shift to the left and right by 1 while multiplying and dividing by 1125899906842624 is a bitwise shift to the left and right by 50.

Our b value starts at a lowly 1 in binary. We need to eventually shift it to be 100, to be 4, however as said earlier the ‘walls’ of 1s in the constant c block us. If our singular bit ever lines up with a 1 bit in the c constant, the result of b&c will be nonzero, multiplied by 1125899906842622, and completely mess up our quest to reach 4. So, our goal is to shift our single bit around in a way to reach 4 and along its journey it can never line up with a 1 bit in the constant c.

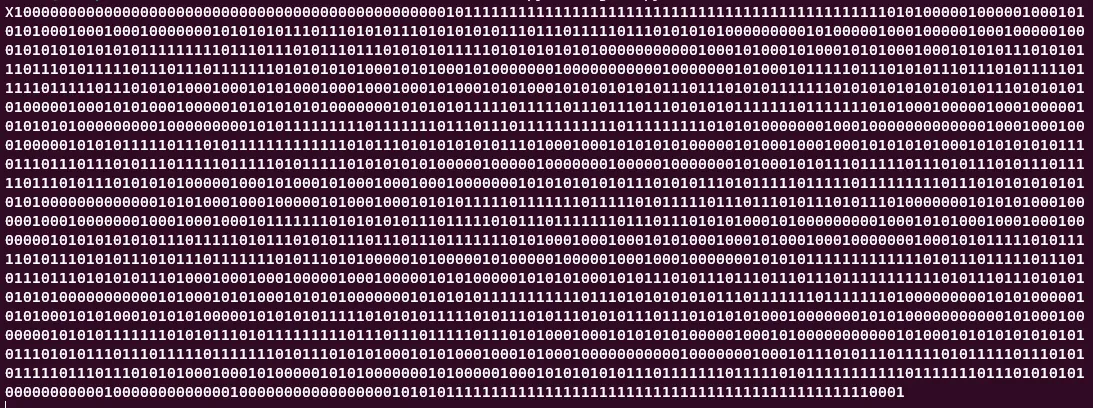

To visualize this idea I made a simple game in python. I have included the file game.py if you would like to try for yourself, but for the purpose of the writeup I will just be showing screenshots. In the game our bit is marked by the ‘X’ character and has 4 possible moves, ‘q’, ‘w’, ‘e’, and ‘r’. Our character can move 50 bits left, 1 bit left, 1 bit right, and 50 bits right respectively. The goal is to move our bit from its starting position as the last bit, to reach the third to last bit:

This is the starting position of our game. As you can see we can’t simply go 1 bit to the right twice as the 1 blocks our way. However we can see there is a long sled of 0s that if reached would allow us to move left until we reached the third to last position. Also note the number in binary is reversed as it just seemed more logically to me when playing around with the game, but it is important to understand that realistically we start at the very end of the number.

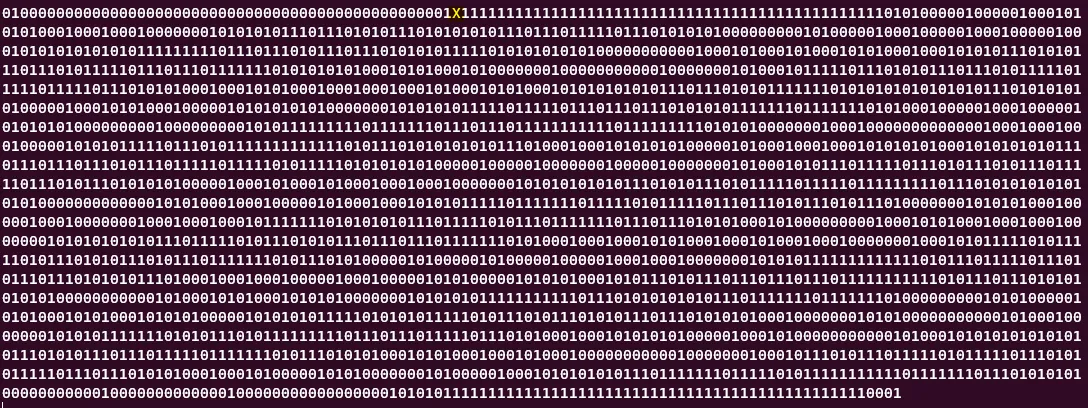

So as our first move we are forced to move right 50:

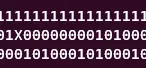

However we are again stuck between 1’s and must move to the right by 50. This will repeat until you find pockets of 0’s as shown below:

However, this is where I realized winning this game manually was going to be a challenge. The first few moves are forced, but eventually the amount of paths branch out just like a maze and sometimes there are so many possible paths at once that keeping track of which ones continue and which ones end becomes impossible to manage. So time to write a script to solve it for us. However now this will be very easy to write as we understand exactly what is happening now that we’ve visualized it from the maze perspective.

For this I used dfs as I am familiar with it and it is very easy to implement.

c = 211403263193325564935177732039311880968900585239198162576891024013795244278301418972476576250867590357558453818398439943850378531849394935408437463406454857158521417008852225672729172355559636113821448436305733721716196982836937454125646725644730318942728101471045037112450682284520951847177283496341601551774254483030077823813188507483073118602703254303097147462068515767717772884466792302813549230305888885204253788392922886375194682180491793001343169832953298914716055094436911057598304954503449174775345984866214515917257380264516918145147739699677733412795896932349404893017733701969358911638491238857741665750286105099248045902976635536517481599121390996091651261500380029994399838070532595869706503571976725974716799639715490513609494565268488194

maze = bin(c)[2:][::-1]+'x'*50

def dfs(pos,moves):

inp = moves[-1]

if inp == 'r':

if (maze[pos+50]=='0'):

pos+=50

else:

return

elif inp == 'e':

if (maze[pos+1]=='0'):

pos+=1

else:

return

elif inp == 'q':

if (maze[pos-50]=='0'):

pos-=50

else:

return

elif inp == 'w':

if (maze[pos-1]=='0'):

pos-=1

else:

return

if pos == 2:

print(moves)

return

if inp != 'q':

dfs(pos,moves+'r')

if inp != 'w':

dfs(pos,moves+'e')

if inp != 'r':

dfs(pos,moves+'q')

if inp != 'e':

dfs(pos,moves+'w')

dfs(0,'r')There are 3 main sections of my dfs function. The first section checks the last move inputted and moves our bit accordingly if possible. If the move would result in colliding with a 1, the function immediately returns as this is not a possible move. The next section is our base case, if we have successfully reached our goal and our bit is in the second position, so 2^2 = 4 we print the moves used to reach there and return. The final section calls the function recursively with all 4 possible moves. I added additional if statements as after debugging I realized some branches would be stuck undoing the move just made so going left-right-left-… forever. These checks ensure that every iteration a new move must be made and no infinite loops occur.

Running this script gives me a solution to our maze almost insantly. The correct order of moves is:

rrrreeeerrrrrreerrwwwwqqwwrrrrrrrrrrrreeeerreeeeeeeeeerrrreerreerreeqqeerreerrwwrrrrrreeeeeerreeeerrwwrrrreeeeeeeeqqwwqqeeeeeeqqqqqqeeeerrrrrrrrrrreeqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwHowever we must remember the script given takes in a number a as input and not instructions. This had me worried at first, but looking back at the script, at every iteration only the last two bits of our input number matter. The operation a&1 only checks if the last bit is 0 or 1 and a&2 does the same but for the second to last bit. Then, the 2 possibilites for the 2 if statments give us a total of 4 possible operations every iteration. Finally, after every iteration, the operation a //= 4 occurs. However, if we remember to frame this problem in terms of binary, just like b //= 1125899906842624 is equivalent to b >> 50, the operation a //= 4 is equivalent to a >> 2. So, every iteration we check the last two bits of a then remove the last two bits of a, and this pattern repeats. This makes it very easy for us to reconstruct our input based off our moves given by our previous script.

To translate our game moves to a binary string I went back to the script to determine which bits have to be set to make which move and I ended up with the following:

q = a&2 > 0 and a&1 > 0 = 11w = a&2 == 0 and a&1 > 0 = 01e = a&2 == 0 and a&1 == 0 = 00r = a&2 > 0 and a&1 == 0 = 10

I quickly implemented this into a script to generate our correct input a:

ops = 'rrrreeeerrrrrreerrwwwwqqwwrrrrrrrrrrrreeeerreeeeeeeeeerrrreerreerreeqqeerreerrwwrrrrrreeeeeerreeeerrwwrrrreeeeeeeeqqwwqqeeeeeeqqqqqqeeeerrrrrrrrrrreeqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwww'

binary = ''

for i in ops[::-1]:

if i == 'w':

binary += '01'

elif i == 'r':

binary += '10'

elif i == 'e':

binary += '00'

elif i == 'q':

binary += '11'

print(int(binary,2))This gave me the number:

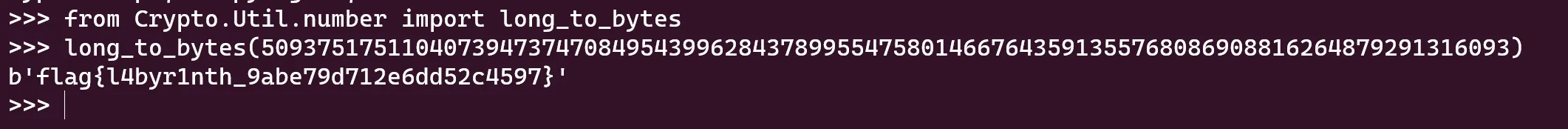

266389209626964670411229630383277269677501566076407503706285515444076594421701235243486016983041387987424513152591848742324465668841041551073869994Inputting this into the original script provided prints: 50937517511040739473747084954399628437899554758014667643591355768086908816264879291316093 and the program terminates. This means we have provided the correct input. I intially tried submitting this number as the flag, but it turned out to just need the good ol’ l2b to finish the job.

There’s our flag! This was definitely a very fun challenge and although this could probably be solved naively with dfs from the start I think the binary maze perspective makes it a much more interesting solve.

stone-games-with-friend

-

Challenge Author: Jaysu

-

Challenge Description: Flag is the output for

input.txt, wrapped in the flag format.

Research

To begin we of course read the .pdf provided. The general premise of the problem is that two players play a series of 30 games. In each game there are piles of stones. Every turn, a player may remove anywhere from 1 to stones, where is the number of stones currently in that pile. This will continue until all piles reach 0 stones and the first player that has no stones to take anymore loses. Both players play optimally and player 0 goes first. For each of the 30 games we are given the amount of piles and the amount of stones in each of the piles. The flag will be an integer made up of the bits based on which player wins each game.

My competitive programming skills are not that strong, so I relied heavily on research to get me through this challenge. It is quickly obvious that this challenge is a variation of the popular game Nim. The only difference is that instead of being able to take any amount of stones > 1 as is in traditional nim, we are limited by the rule described earlier. There are plently of resources and similar problems online, but throughout my time I really only ended up using two very valuable resources that explained everything I needed to know for this:

- https://codeforces.com/blog/entry/66040

- https://math.stackexchange.com/questions/704870/winning-a-restricted-game-of-nim

If you are curious you can read each individually, but I will reference the most important points of each. I knew I was on the right track with the CF blog as they even said, “A common tweak is putting a limitation on the number of stones you can get from a pile.” This is exactly what our challenge is, so I knew this was on the right track. All of the Nim-related games described in the blog are called impartial games, this means that the games are decided purely by how the game is setup, in our case the number of stones in each pile, and which player goes first. There is a lot of studied game theory on impartial games, but we really only need to reference the basics.

Another important quote from the blog was, “these games are equivalent to playing Nim, but instead of getting the Nim-sum by taking the XOR of the piles, we take the XOR of their Grundy numbers.” So really the tl;dr solution for these problems is to split the game into individual piles and calculate the Grundy numbers for each one and XOR all of them, if the result is nonzero one player will win, if the result is zero the other player wins. Throughout my solution I won’t specifically reference when player 0 or 1 wins as it doesn’t really matter until we construct our flag at the end and we can always simply flip our bits if our flag is incorrect.

So, we know how to get the solution, but what are Grundy numbers? These were explained in the CF blog, but I was really just looking for an easy method to write a script to calculate them and the CF blog didn’t do that as well. Enter the math stackexchange question. There the question describes a Nim variation where you can take only 1 or 2 objects from the pile every turn. After reading the top answer this is how I understood calculating Grundy numbers:

To calculate the Grundy number for a pile of size , first find all possible positions that can be reached after one player’s turn. In our case, the possible positions range from to . Now that we have our possible positions, calculate the Grundy numbers for all of those positions and then take the minimum excludant (mex) of those. The result of that will be our Grundy number. Quick note: if you are unfamiliar with the mex function it is essentially the first nonnegative integer in a set, basically start at 0 and keep incrementing until you can’t find that number in your set and that will be your mex.

So we now know how to calculate Grundy numbers, but one issue that becomes quickly apparent is the recursive nature of this “Grundy function”. Given a very large N value we will essentially need to calculate the Grundy value for every number 0 to N. This is because the Grundy for N is reliant on N-1, N-2, … N-floor(sqrt(N)), and then N-1 is reliant on N-2, N-3, … and you get the idea. But this is no problem right, python can do recursion. Time to write our solution!

Solution

I quickly wrote a python script that would recursively find Grundy numbers and store them in a large array. By the way one thing I may have left out is the Grundy of 0 is simply 0 which acts as our base case for recursion. This worked great and I was able to generate the Grundy numbers up to 1,000, 10,000, 100,000 and oh this is taking a while. It very quickly became apparent that this program was going to be very very slow. But not to fret, we are given input.txt so it is okay if our solution is very long. But checking the .pdf again, the piles can go up to sizes of . If my script took an hour to calculate the Grundy for 1 million, 1 billion was never going to happen.

I referenced the CF blog again and they even say: “The complexity in these kinds of programming problems in contests usually then comes down to finding some efficient formula for the Grundy numbers.” And this was the exact problem I had run into. After a lot of head banging I eventually made a key observation when I looked at the first 100 Grundy numbers that my script generated:

[0, 1, 0, 1, 2, 0, 1, 2, 0, 3, 1, 2, 0, 3, 1, 2, 4, 0, 3, 1, 2, 4, 0, 3, 1, 5, 2, 4, 0, 3, 1, 5, 2, 4, 0, 3, 6, 1, 5, 2, 4, 0, 3, 6, 1, 5, 2, 4, 0, 7, 3, 6, 1, 5, 2, 4, 0, 7, 3, 6, 1, 5, 2, 4, 8, 0, 7, 3, 6, 1, 5, 2, 4, 8, 0, 7, 3, 6, 1, 5, 2, 9, 4, 8, 0, 7, 3, 6, 1, 5, 2, 9, 4, 8, 0, 7, 3, 6, 1, 5]If you look closely at these a pattern begins to emerge. The pattern does have some complexity to it, but it was definitely something I could script. I’m not sure if this is the best way of describing it, but this is how I ended up thinking about the pattern myself and how I wrote my script later. Rule #1 is that as we are generating our list of Grundy numbers we want to keep track of our “subpattern” I’ll call it. When we first start our subpattern is simply [0]. So if we generated just using rule 1 we’d get [0,0,0,0,0,...]. Enter Rule #2: at any index that is a perfect square, add the squareroot of that index to our subpattern from rule 1 and continue.

To explain it better I’ll walk through the first couple of Grundy numbers:

- Index: 0, Subpattern:

[0], Add 0 to array. - Index: 1, Perfect Square!, Subpattern:

[0,1], Add 1 to array. - Index: 2, Subpattern:

[0,1], Add 0 to array. - Index: 3, Subpattern:

[0,1], Add 1 to array. - Index: 4, Perfect Square!, Subpattern:

[0,1,2], Add 2 to array. - …

- Index: 9, Perfect Square!, Subpattern:

[0,3,1,2], Add 3 to array. - …

- Index: 16, Perfect Square!, Subpattern:

[0,3,1,2,4], Add 4 to array.

So we are essentially continuously cycling through our subpattern and appending numbers to our main array, until we reach an index that is a perfect square. If a perfect square index is hit, the subpattern has a new number inserted at whichever index was last appended to the main array. This continues forever and works in linear time and is thus able to calculate all Grundy numbers up to very quickly. This is how I implemented this idea into my Grundy generation script:

grundys = [0,1]

subpattern = [0,1]

index = 0

for i in range (2,1000000000):

sq_root = perfect(i)

if sq_root == -1:

grundys.append(subpattern[index])

else:

grundys.append(sq_root)

if index == 0:

subpattern.insert(len(subpattern),sq_root)

index -= 1

else:

subpattern.insert(index,sq_root)

index += 1

index %= len(subpattern)It took some trial and error, but eventually this script was generating an array of Grundy numbers identical to my recursive solution, but significantly faster. I made some minor tweaks to this base script to only print out Grundy numbers I needed, those being all of the pile sizes in input.txt, as I didn’t want to print out 1 billion Grundy numbers. You can find the full script grundy.py in the same folder as this writeup. Once I had all the Grundy numbers I needed, it was just a matter of XOR’ing them and checking if the result was zero or non-zero:

#grundy = [Very large array generated by grundy.py, not shown here]

out = ""

f = open('input.txt','r')

g = int(f.readline().strip())

for i in range (g):

game = f.readline().strip().split()

n = game[0]

game.pop(0)

game = list(map(int,game))

xor = 0

for j in game:

num = -1

for h in grundy:

if h[0] == j:

num = h[1]

break

if num != -1:

xor ^= num

else:

print("AHHH")

if (xor != 0):

out = '0' + out

else:

out = '1' + out

print(int(out,2))This took more trial and error and rereading the pdf to know the exact input and output specifications, but eventually I had my flag!

Flag: flag{67643916}

This was a very fun challenge and well-designed as CTF players like me who aren’t as familiar with algo are able to have plenty of resources available, yet still have some challenge ahead of them. Thanks Jaysu!